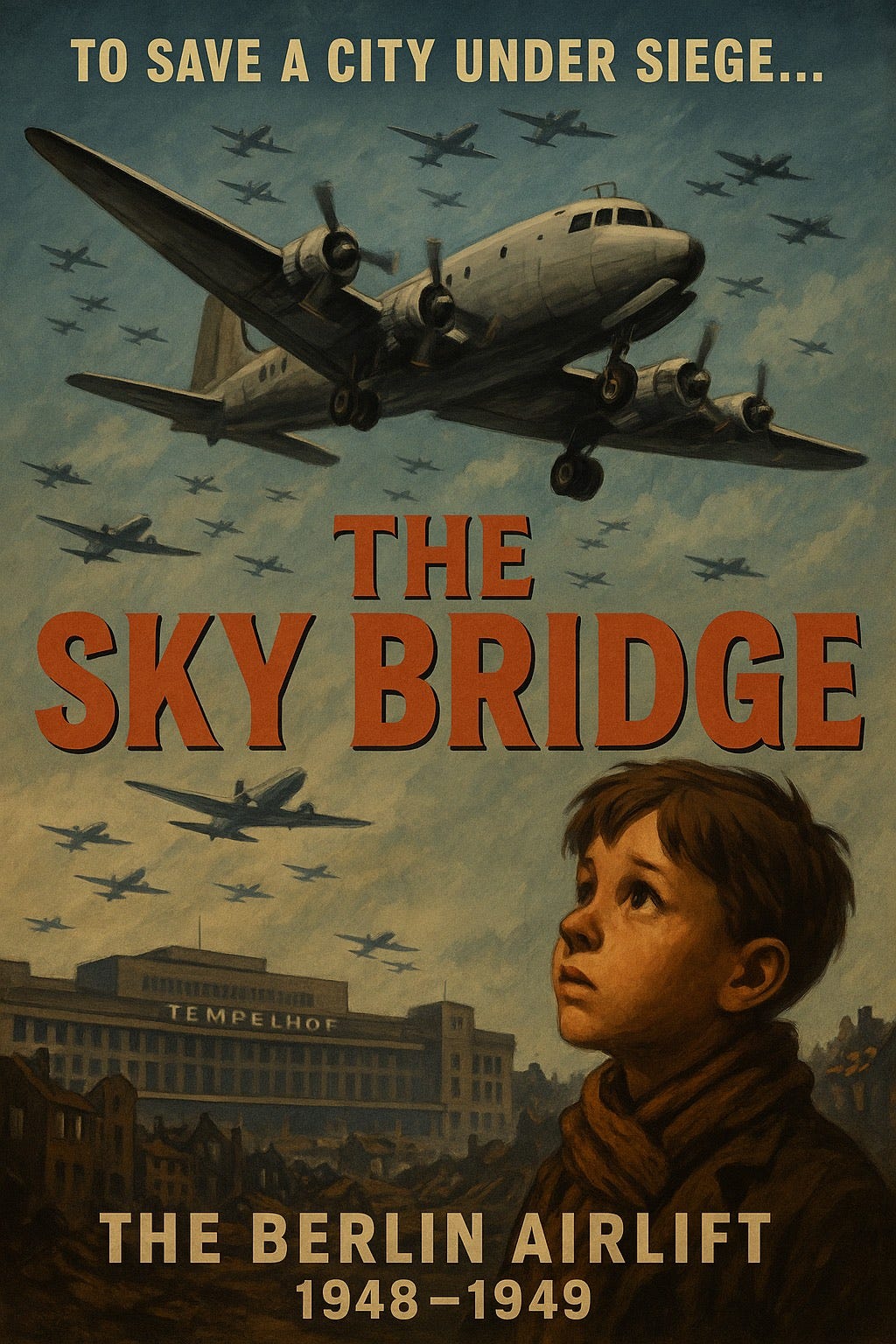

The Sky Bridge

How America Saved Berlin

Berlin, Summer 1948

The lights flickered once. Then they died.

A low rumble passed through the streets like a distant warning. Streetcars ground to a halt, bakery ovens fell cold, and radios turned to silence. The hum of a once-recovering city disappeared. In the markets, whispers turned to panic.

In one swift motion, Stalin had sealed the border.

Roads wer…