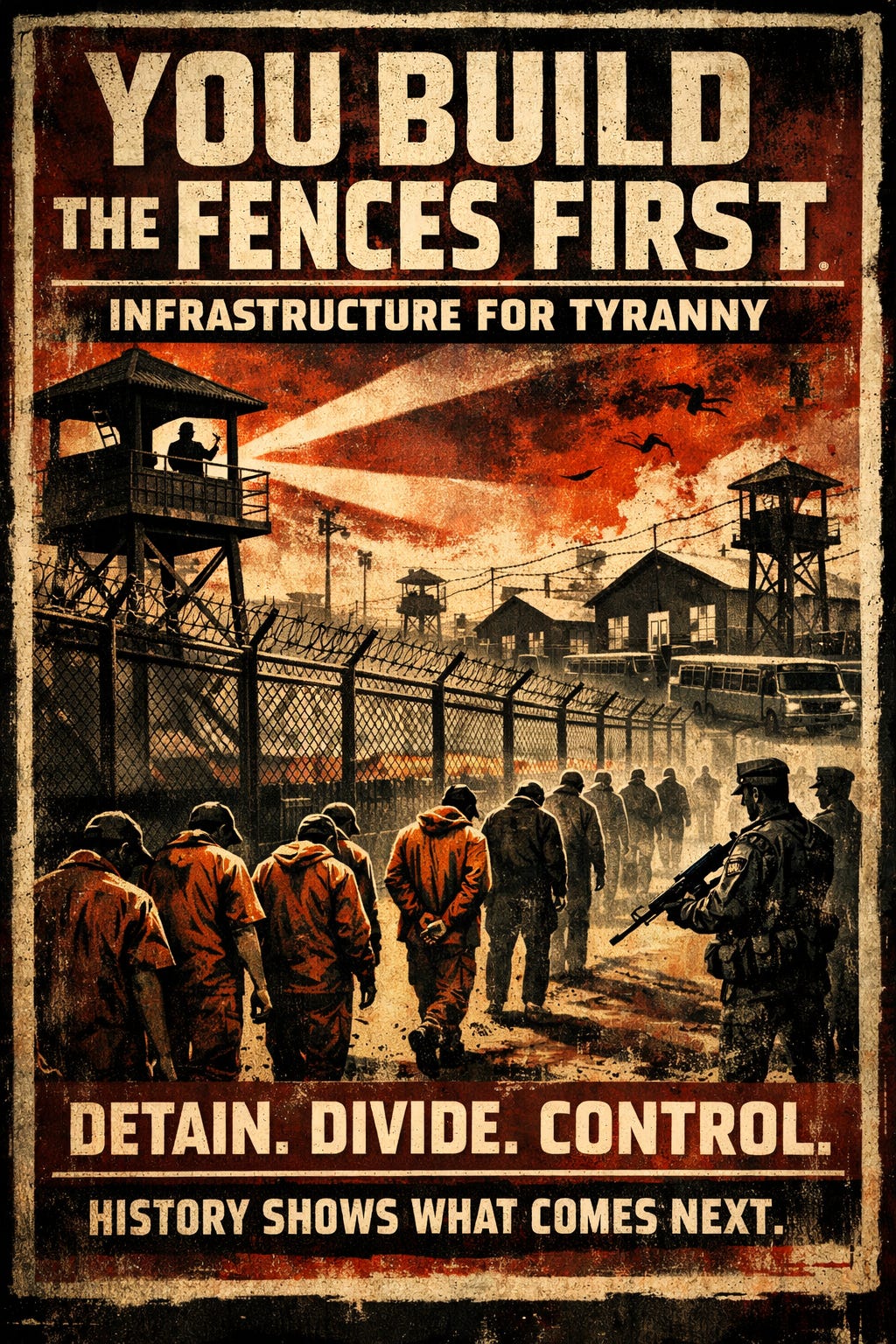

You Build the Fences First

Infrastructure for Tyranny

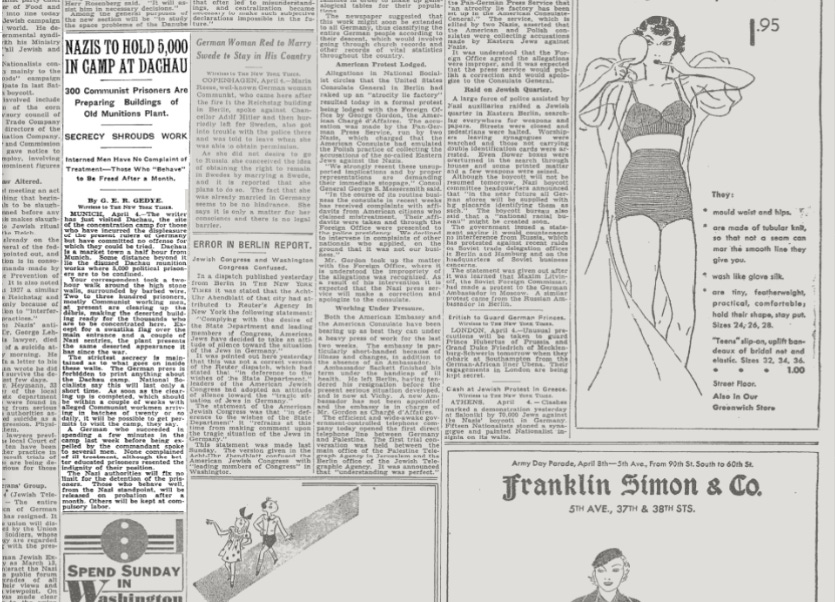

In 1933, the Nazis did not hide Dachau.

They invited outsiders to see it.

Foreign correspondents were escorted through the newly opened Dachau Concentration Camp and shown neat barracks, orderly rows of bunks, and prisoners moving through structured routines. Guards stood upright and disciplined. The grounds appeared controlled, even efficient. What visitors saw looked administrative.

The violence — already present — was kept out of sight.

Early outside impressions could therefore be framed in bureaucratic language: order, discipline, containment, political detention. The regime understood something essential: if you shape what observers see, you shape how institutions are understood.

And in 1933, Dachau was not yet a symbol of industrialized mass murder. It was a political detention center. Its prisoners were primarily communists, social democrats, trade unionists, journalists, and critics of the new regime.

The Nazi’s genocidal machinery came later.

First came the infrastructure.

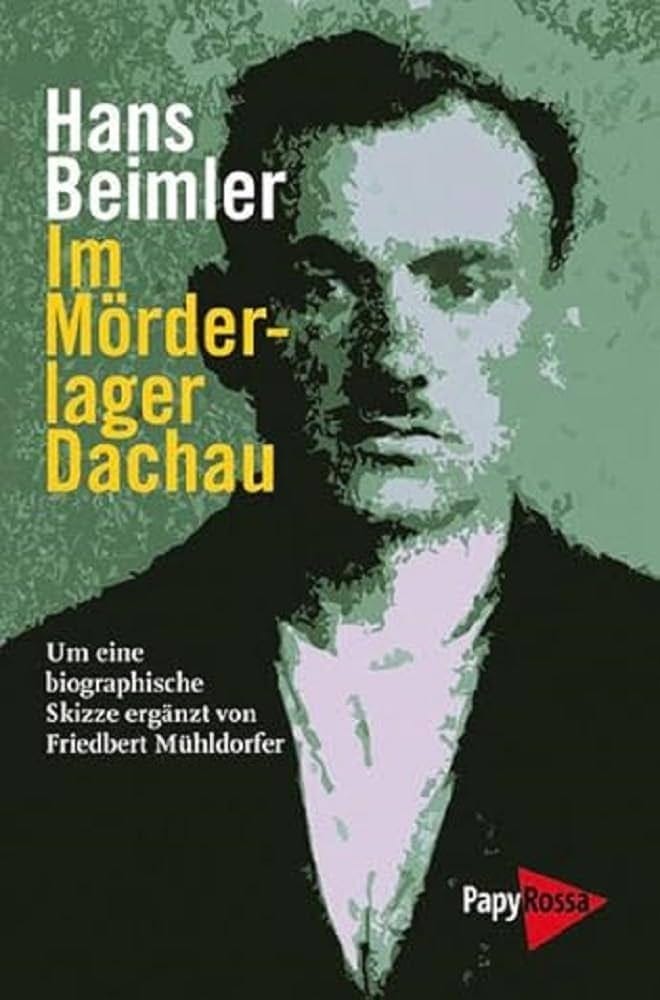

To understand what that infrastructure meant in practice, it helps to look at one of the men who passed through Dachau in its earliest weeks.

Hans Beimler, a Communist member of the Reichstag, was arrested in April 1933 and taken to Dachau shortly after the camp opened. His experience bore little resemblance to the orderly image shown to visitors.

He was beaten repeatedly by guards. Prisoners were forced to stand for hours in rigid formation. Punishments were arbitrary and unpredictable. Violence was not incidental — it was routine. Beimler later described an environment designed to terrorize and dominate prisoners physically and psychologically.

He eventually escaped and fled Germany. His published account was one of the earliest eyewitness descriptions of what the camp system actually was: a place where legal restraint had largely disappeared and administrative authority had few limits.

But most people outside Germany did not read Beimler’s testimony.

They saw what they were shown, what the Nazi’s wanted them to see.

That gap — between presentation and reality — is where normalization begins.

There is a pattern to how detention systems grow.

They do not begin as death camps. They begin as administrative responses to crisis.

After the Reichstag Fire, the Nazi government issued the Reichstag Fire Decree, suspending civil liberties and allowing detention without meaningful judicial oversight. Arrests followed. Thousands of political opponents were detained and placed in improvised holding sites — old prisons, military barracks, abandoned industrial buildings.

Dachau became the model that standardized everything: intake procedures, guard training, disciplinary systems, classification categories. It was scalable. Bureaucratically legible. Repeatable.

And most Germans were never imprisoned there. Most believed the system was targeted, necessary, and temporary.

That belief — that detention is for someone else — is what allows the system to stabilize.

Other regimes followed similar institutional paths. The Soviet Union built the Gulag — not a single camp but a vast network administered by a central bureaucracy whose name literally meant “Main Administration of Camps.”

The Gulag was not primarily designed as a mechanized extermination system. It was a forced labor regime. Prisoners mined, logged, built infrastructure, and worked in extreme environments with inadequate food, clothing, or medical care.

But when human beings are treated as expendable labor inputs, death becomes routine. Millions died through starvation, exhaustion, exposure, and disease. Survival was not structurally prioritized.

The method differed from industrialized killing.

The outcome — mass death produced through confinement and forced labor — did not.

And again, the system began with administrative justification: political enemies, economic offenders, class threats. Categories that could expand.

They always expand.

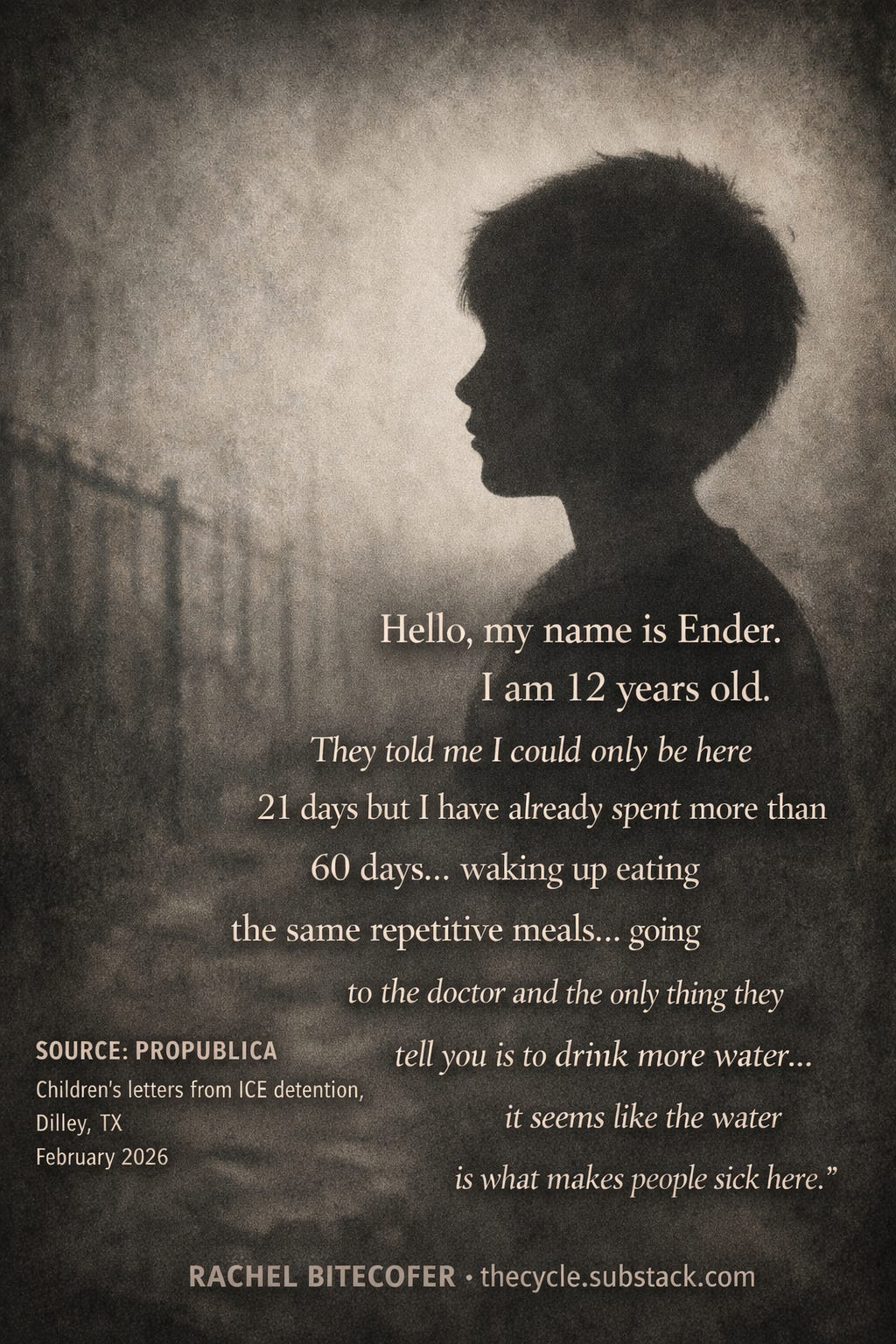

Now, snap back to the United States in 2026.

What is being built today is not a minor enforcement adjustment. It is not a temporary surge response. It is a large-scale expansion of detention capacity backed by enormous capital investment.

Plans call for roughly $38 billion in new detention infrastructure. The system is designed to support about 92,600 detention beds nationwide, more than double the capacity that existed only a few years earlier.

This is not short-term management.

This is architecture.

What Is Actually Being Built

When we talk about tens of billions of dollars in detention expansion, it is easy to imagine simply “more facilities.”

That understates what is happening.

This is system design.

Federal authorities are planning an integrated detention network structured to receive, process, hold, and transfer large numbers of people continuously.

Industrial warehouses are being purchased or leased and retrofitted for confinement. These are logistics structures — designed for rapid conversion and high throughput.

Large regional processing centers are planned to receive detainees from wide geographic areas, conduct intake and classification, and route individuals onward. These processing facilities are designed for short stays — often only three to seven days — before transfer.

Larger detention centers are designed for longer holding periods, sometimes up to several weeks, before further movement through the system.

Facilities are frequently located in rural or remote regions, where oversight is limited and detainees are geographically isolated from legal and social support.

Transport infrastructure — buses, coordinated transfers, routing between facilities — is integral to the design. Detainees are not simply confined; they are moved through a managed pipeline.

Private contractors operate major components of the system — facilities, security, medical services, logistics. Long-term federal contracts embed detention operations into local economies and institutional budgets.

Staffing pipelines expand alongside construction. Guards, intake personnel, administrators, transport coordinators — a workforce built to operate the system continuously.

And beneath all of it is administrative structure: classification procedures, intake documentation, transfer authority across jurisdictions, and legal mechanisms that allow confinement to proceed rapidly.

This is not episodic enforcement.

It is permanent capability.

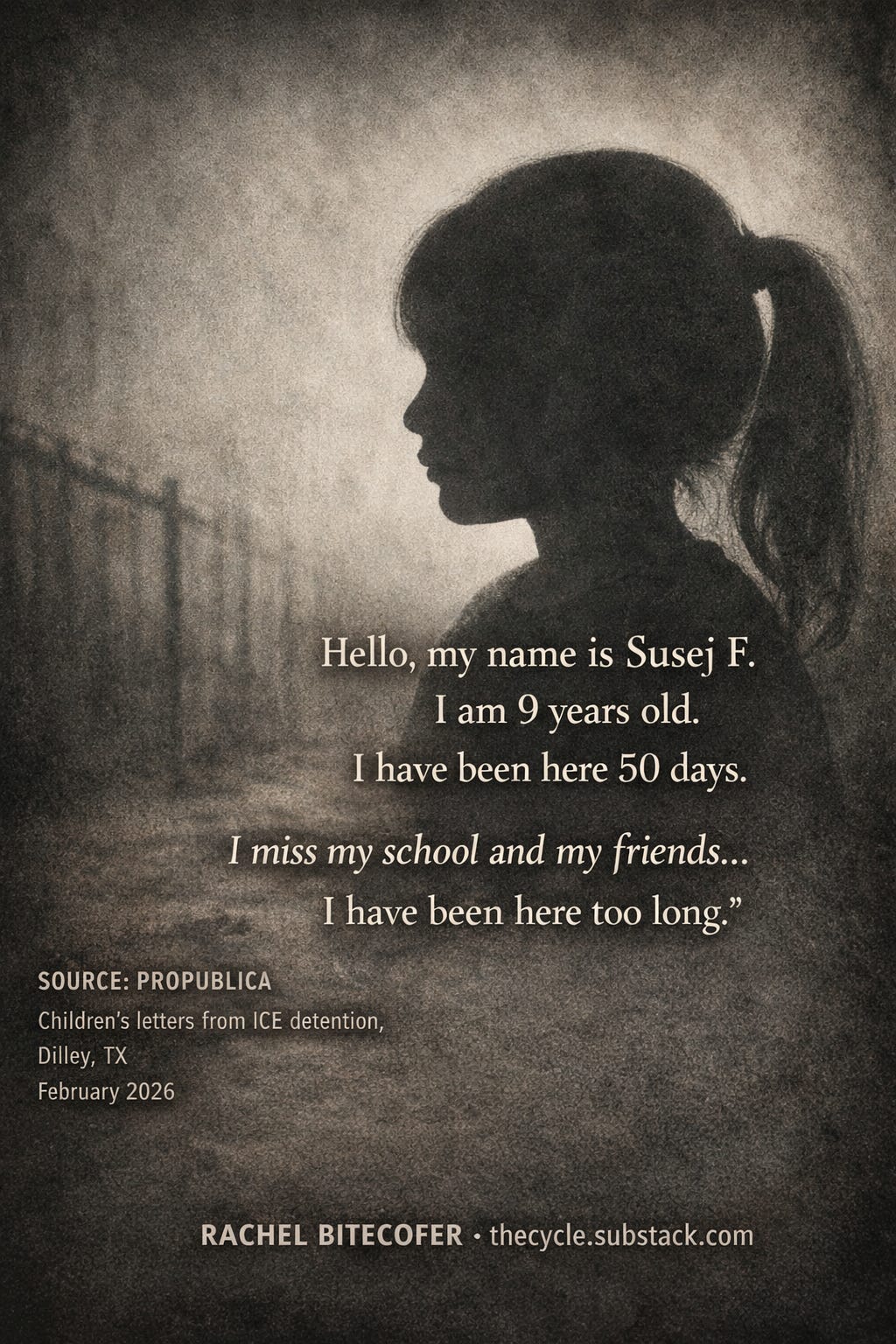

The public justification is simple: illegal immigrants.

That phrase performs essential political work. It marks a population as outside ordinary protection. It reassures everyone else that detention is targeted and procedural.

But detention systems do not remain fixed to their initial category.

In Germany, early camps held political enemies. Later they held others. The infrastructure did not change. The classification did.

In the Soviet Union, the Gulag expanded through administrative redefinition — new offenses, broader categories, larger quotas.

Infrastructure makes expansion easier than restraint.

Detention is not merely a step toward deportation. It is power.

Detention allows authorities to hold first and adjudicate later. To move individuals far from legal representation. To separate them from families and support networks. To apply pressure through confinement.

Once physical capacity exists, using it becomes easier — politically, legally, bureaucratically.

Expansion rarely arrives as a dramatic announcement. It happens through incremental adjustments — new enforcement priorities, revised definitions, widened discretion.

Each change appears limited. The cumulative effect is not.

The early presentation of Dachau shows how normalization forms. The system appears orderly, rational, controlled. Harsh realities are hidden. The language is administrative. Observers see what they are permitted to see.

By the time the full character of a detention system becomes undeniable, the infrastructure is already permanent.

The guards are trained. The facilities are staffed. The budgets are embedded. The public is accustomed.

And most people still believe it exists for someone else.

And once places to concentrate detainees outside of the normal legal system reaches scale, they become enduring instruments of state power that can be deployed against anyone.

A detention network built at this magnitude is not a temporary response. It is a structural shift in what government can do.

You do not build a system this large for a moment.

You build it for an era.

You build the fences first.

History shows what can follow.

Already a subscriber?! Help me grow The Cycle by sharing this post with your friends and family!

Thanks, Doc. A new purchase is a warehouse in San Antonio. The City Council says they can do nothing, that the federal regime is immune to any legal response.

REALLY?

"With the first link, the chain is forged. The first speech censured, the first thought forbidden, the first freedom denied, chains us all irrevocably." - Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "The Drumhead"